Donald Trump’s ‘unpresidented’ rise to power has seen an entire government administration built on logical fallacies.

Flawed arguments are wall-to-wall in the Trump era: Circular reasoning. Appeal to fear. Appeal to ignorance. OMG the ignorance.

Traditionally, it’s the responsibility of the fourth estate (the media) to save us from such rhetorical trickery. Trouble is, the media is so used to trafficking in logical fallacies of its own, that many journalists seemed incapable of inoculating themselves against Trump & Co’s uniquely dangerous word salad in the run-up to last year’s bombshell election.

An estimated 1 million people globally participated in the March for Science on 22 April 2017.

In fact, the logical fallacy in the media that is partially responsible for electing current US President – and noted climate change denier – Donald J. Trump is the very same fallacy that has delayed action on climate change for decades: false equivalence.

False equivalence is what happens when two things are presented as if they share equal validity or weight, when in fact they don’t.

Take the 2016 US election as an example:

Donald had (has) the racism, the misogyny, the Islamophobia.

“BUT HER EMAILS,” the anchors squawked.

And when applied to the climate change discourse, false equivalence looks like this:

“Anthropogenic climate change is real,” agrees a global consensus of roughly 97% of scientists.

“BUT LET’S HEAR FROM THIS ONE OLD WHITE GUY WHO THINKS IT’S ALL A HOAX,” the news producers sputter.

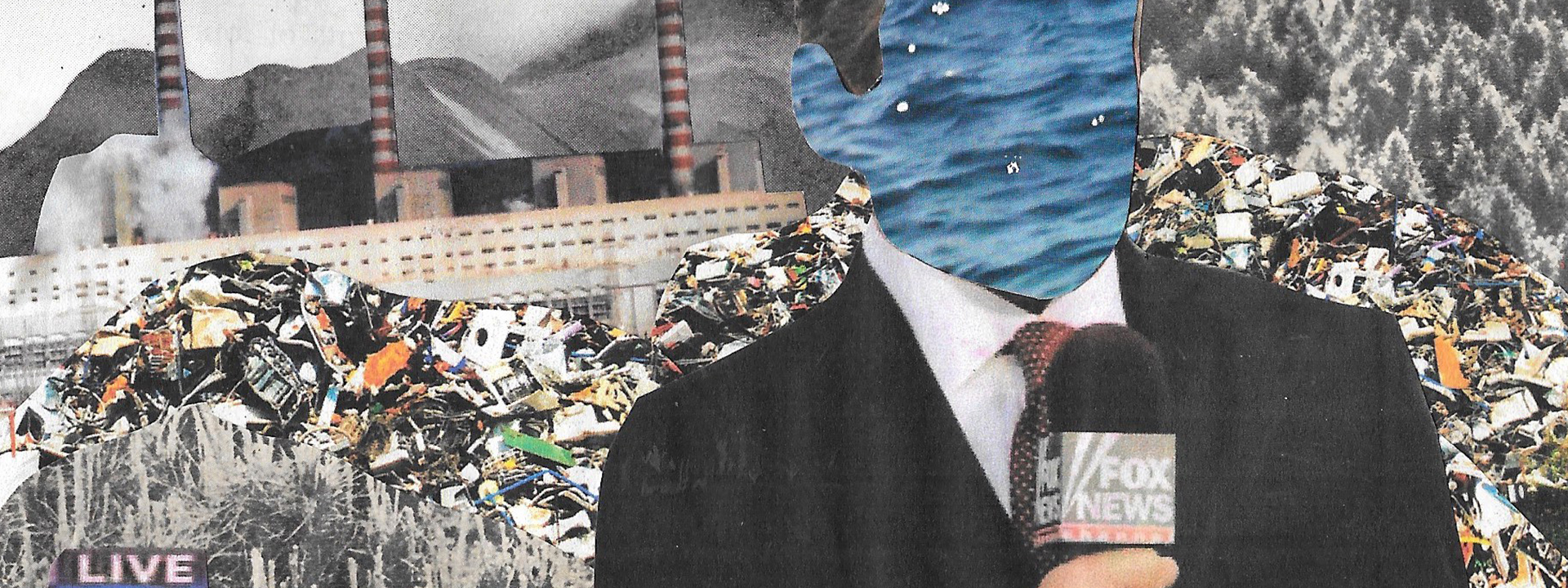

Illustration by Marta Parszeniew

The media, and especially TV, generally follows a formula when it comes to covering the news of the day. Issues are framed as debates, with two opposing sides argued by two opposing people armed with varying degrees of fervour and (alternative) fact.

This false balance happens even when the facts overwhelmingly favour one side of a so-called ‘debate’.

But because journalists fear accusations of bias the same way Sean Spicer fears journalists, their desire for objectivity can, rather perversely, produce the opposite effect.

And for more than three decades, this is exactly what has been happening with climate change reporting.

WE ARE THE 97%

Studies show that the more expertise a climate scientist has, the more likely they are to believe in man-made climate change.

By giving climate change experts with legitimate, proven concerns equal billing to climate change deniers (who often come with much flimsier qualifications, representing institutes bank-rolled by corporate interests), journalists fatefully conflated objectivity with neutrality – and buried the truth in the process.

The media has enormous power in shaping public belief and attitudes, especially about complicated ideas of which the audience has little direct experience.

By constructing an equal playing field where there should never have been one, journalists constructed a sense of public uncertainty about the validity and urgency of climate change. They gave their audience a choice between worrying about a big, scary and complicated science-y thing, or not worrying about it at all because it may not exist.

“I will say, much as I love CNN, you’re doing a disservice by having one climate change skeptic, and not 97 or 98 scientists or engineers concerned about climate change.”

Science communicator Bill Nye, arguing for more representative reporting on CNN’s ‘New Day’

We now know that this kind of false balance in reporting damaged the prospects of climate action for decades. With fewer people convinced that the problem was real, fewer people felt compelled to make sustainability-related changes to their lifestyle, and fewer people demanded that their elected officials view climate change as a policy priority.

When Al Gore’s Oscar-winning documentary about climate change An Inconvenient Truth came out more than a decade ago, it cited a database search of newspapers and magazines in which 57% of relevant articles questioned the fact of global warming, while just 43% supported it.

According to Gore and others, these figures were the result of a years-long disinformation campaign by the energy industry to ‘reposition global warming as a debate’. Of course, because of its penchant for false equivalence, the media was the main channel through which that disinformation campaign was so successfully amplified and spread.

Heineken’s new ad campaign uses false equivalence masquerading as ‘progressivism’ to market its beer.

In his four-star review of An Inconvenient Truth in 2006, beloved film critic Roger Ebert noted that the logical fallacy at play in climate change reporting was familiar. He wrote, “It is the same strategy used for years by the defenders of tobacco. My father was a Luckys smoker who died of lung cancer in 1960, and 20 years later it was still ‘debatable’ that there was a link between smoking and lung cancer. Now we are talking about the death of the future, starting in the lives of those now living.”

Today, not long after the release of Gore’s latest film, An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power, it’s clear that the flavour of public discourse on climate change has shifted, but the media’s power, and its potential for harm, remains.

Illustration by Marta Parszeniew

DID I DO THAT?

People in countries with the highest per-capita levels of carbon emissions are the least concerned about climate change.

Because, despite the fact that the percentage of Americans worrying ‘a great deal’ about global warming is at a record high, and despite the fact that most scientists are now joined by major energy companies and even some conservatives and members of the right-wing media in acknowledging the reality of climate change, climate skeptics still stubbornly refuse to endorse meaningful action to tackle it.

The facts on climate change are unequivocal – no matter what Trump’s EPA Chief says. So skeptics are waging the war on new grounds. Instead of a true-or-false face-off, the climate change ‘debate’ now centres on the question of ‘What are we going to do about it then?’

Former deniers now operate as obstructionists. They stipulate the facts of climate change, but argue that most policies to tackle it would be:

- too expensive for taxpayers,

- too costly for industry and jobs,

- too speculative – ‘we’re not even certain it would work’,

- too unpopular with a public who does not want to give up all the trappings of the consumerist lifestyle to which they have grown accustomed.

These moments of obstructionism occur on both sides of the Atlantic, and in most major broadcasts and publications of record: from The Telegraph’s Turnbull to the mythical Nigel Lawson on the BBC and even in the storied pages of The New York Times.

In the first of his column for that paper, conservative writer Brett Stephens deployed a basket of deplorable fallacies to argue against action on climate change, opting instead to call into question the very nature of scientific consensus, labelling that certainty a form of hubris that will choke off all possibility of an honest debate.

BBC Scotland programme editors were told not to feature debates between climate scientists and sceptics because they would amount to false balance.

CALL THEM BY THEIR NAME

The Associated Press has decided to start using the sanitised term ‘doubter’ rather than the more damning ‘denier’.

By seeking to undermine climate action in the name of ‘probabilism’ (academic skepticism) and ‘proportionality’, Stephens demonstrates exactly how denialism has rebranded itself for the 21st century.

And what’s worse – even when a misleading argument is later debunked or retracted, we often continue to believe the original lie. Psychologists call this the ‘backfire effect,’ and it happens in climate change reporting a lot.

It is all highly cynical – and very scary.

Because they don’t have to win the argument. Deniers’ principle product, whether they’re the journalist or the guest, is doubt; all they have to do is create enough confusion in the minds of the public so that people lose any urgency about attempting to solve the crisis.

Illustration by Marta Parszeniew

So, what are we going to do about it then?

Luckily for us, print media is dying. (Jokes…well, sort of).

TV displaced print as the dominant news medium in the 1960s, but now its own influence is waning in the Internet age, as more and more young people turn to new and social media.

That’s not to say that newer media outlets are necessarily any better at avoiding false balance when it comes to climate change reporting. What it does tell us, however, is that it’s only a matter of time before mainstream media relinquishes its control over the narrative, thereby limiting its ability to shape public opinion in the same way it has for decades.

In 2014, US Senator Jim Inhofe brought a snowball into the chamber as evidence that climate change was a hoax.

And that’s a good thing. Since the 1980s, the media’s compulsion to appear ‘balanced’ on global warming has contributed to public confusion, ambivalence and inaction on climate change. In our post-truth era and politicised media landscape in which climate deniers have the loudest microphones and occupy the highest positions of power (basically Trump’s entire cabinet in the US; the DUP, who hold the balance of power in the UK, and many other high-ranking Conservatives), we need a multiplicity of voices to drown out their highly strategic skepticism.

Of course, the task to move an apathetic public to action becomes easier the more they experience the effects of climate change. When communities are facing ‘once-in-500-years’ events year after year – Mother Nature does the persuading for us, and soon people will start to ask the questions, and demand the answers, that some journalists have so far failed to do.

THE BLIND LEADING THE BRITS

The UK government has appointed Dieter Helm, a vocal critic of wind and solar power, to lead its review of the financial cost of energy in the UK.

A journalist’s job is to report the truth. But the truth rarely lies in the centre of an argument. That’s why those in charge of informing the public – producers, editors, commissioners and of course the journalists themselves – must do away with the idea of ‘balance’ as a substitute for ‘truth’.

They must remember that there is simply no equivalence between the paid-for opinions of a climate change denier and the peer-reviewed facts offered by a climate scientist. Facts that prove climate change is a problem we created, and that it is getting worse.

The media must find the courage to report that without dilution or debate. And their public audience must be more vigilant in holding them to account when they don’t.

Because good science doesn’t lie, but bad Presidents do.

We are #AntiSkeptic

As long as journalists, editors, producers choose to promote the views of skeptics, it’s our duty to hold them to account.

We can take on the media by calling, writing, commenting, petitioning or boycotting. We can defy the deniers by taking green action in our lives.

Watch our #AntiSkeptic explainer, share it and fight the disinformation designed to hold us back.